Decision Architecture: Building Better Choices

Elissa and Dave’s paper on policy-based financial planning was published in the December issue of the Journal of Financial Planning (Policy-Based Financial Planning as Decision Architecture). Financial planning policies are compact decision rules that make it easier to stick with a consistent course of action in the midst of an ever-changing environment. Developing good policies can be thought of as a form of “decision architecture” in which we structure the policies in such a way as to leverage our natural human proclivities, like sticking with default options. As Elissa and Dave note in their paper, how decisions are structured can have an enormous impact on outcomes.

A compelling example of the power of the nudge can be found in an examination of the respective organ donation rates of Germany and Austria (Thaler 2009). According to the European Social Survey, these two countries have a cultural similarity index of 0.846, which would suggest that they are very nearly identical from a social and cultural perspective. However, the organ donation rate in Germany is only 12 percent compared to an Austrian donor rate of 99 percent. The explanation for this difference can be found in the structure of the choices faced by each country’s citizens. The system for electing to be an organ donor in Austria requires individuals to opt out, while Germany requires donors to opt in. This is an example of one of the findings from behavioral finance; namely, that default options and inertia are incredibly powerful forces when it comes to making and acting on decisions.

A well structured policy can take one’s beliefs and the goals that arise from those beliefs and provide simple decision rules that can take the stress out of daily decision making. One area where this can be useful is in the area of charitable giving. As anyone who has become active in charitable giving knows, the check you write is the first of two gifts, the second one being generated when the charity sells your name to a mailing list. The growing number of appeals can become quite stressful unless you’ve adopted formal policies that guide your giving. Here’s an example:

- Belief: Preschool enrichment programs greatly enhance lifetime educational success.

- Goal: To devote a sustainable portion of my annual income to supporting preschool enrichment programs.

- Policy: I will focus my charitable giving exclusively on preschool enrichment programs, and I will annually donate to such organizations an amount not to exceed 10 percent of the annual safe withdrawal spending target for my portfolio.

The person who has adopted these policies can now much more easily deal with the many appeals for support that come along by applying a straightforward, two-part filter: (1) does this organization support preschool enrichment programs; and (2) have I yet donated 10 percent of this year’s safe-spending target?

Policies can be particularly powerful for young people just starting their careers and who’s circumstances with respect to earnings, expenses, and living situation will typically go through many changes in a short period of time. Adopting the right saving polices early can be incredibly powerful. Just note that a young person earning $40,000 per year who starts saving 10% of their earnings at age 25 will accumulate $1,036,000 by age 65 (assuming an 8% rate of return), while waiting until age 30 to start saving results in an age 65 balance of $689,000. The one who started just five years sooner ended up with 50% more savings at 65, truly an example of the power of time (we like to say that young people have a super power – TIME- but it’s one that fades quickly!). Here’s a simple saving policy that we encourage all young people to adopt:

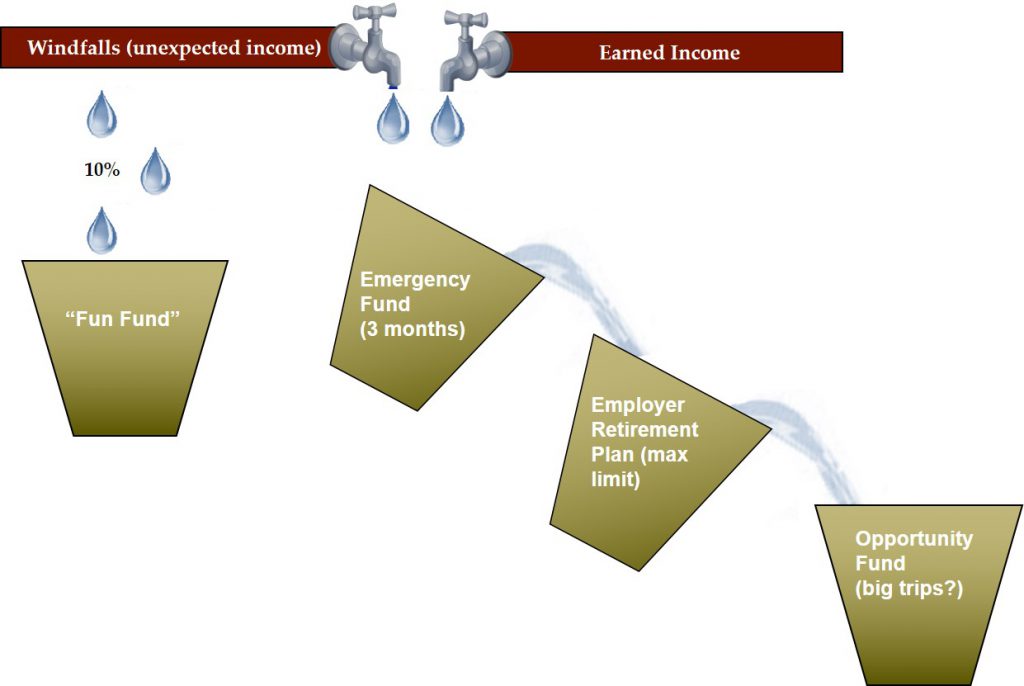

- I will save 10 percent of every paycheck;

- My savings will go first to my emergency fund until the account equals three months’ worth of living expenses;

- Thereafter, my savings will go into my employer retirement plan to the contribution limit;

- Any remaining savings will go into an after-tax opportunity fund;

- Windfalls, such as bonuses, will be allocated 10 percent to a fun fund and 90 percent per the preceding policies.

With this policy, no matter how many changes might occur in the young person’s life with respect to earnings or expenses (and typically there will be many!), they always know exactly what to do. Such a policy can also be thought of and illustrated as a series of cascading buckets.

Policies can also be a useful way to plan for “contingent” resources, those for which the value, timing, and probability of occurrence are highly uncertain (e.g. bonuses, gifts or inheritances, surprise tax refunds, etc.). Policies can be used to establish in advance the appropriate actions to take if the contingent resource materializes. Here’s an example of such a cascading policy that allows the contingent resource to be accounted for in the financial plan, even though it cannot be explicitly incorporated into the financial projections:

Any windfall from (named contingent resource) will be allocated as follows:

- First, toward my nephew’s college fund up to one-half the then projected four-year cost;

- Next, to the American Heart Association up to 10 percent of my then annual earned income;

- Next, to a kitchen remodel up to 5 percent of the house’s then appraised value; and

- Any remaining funds will be added to my after-tax retirement savings account.

The “decision architect” can also design policies to address risk management and the use of insurance, lifetime gifting, and the use of debt, to name a few.

At Yeske Buie, we also use “Safe-Spending Polices” to help us determine the highest, sustainable level of spending available to clients in retirement and to ensure that they remain on a safe and sustainable path.

In the end, well crafted policies can truly become a touchstone to help keep us committed to a consistent course of action as we pursue our life goals.

References

Thaler, Richard H. 2009. “Opting In vs. Opting Out.” The New York Times, September 26